Space Debris

Orbital Objects

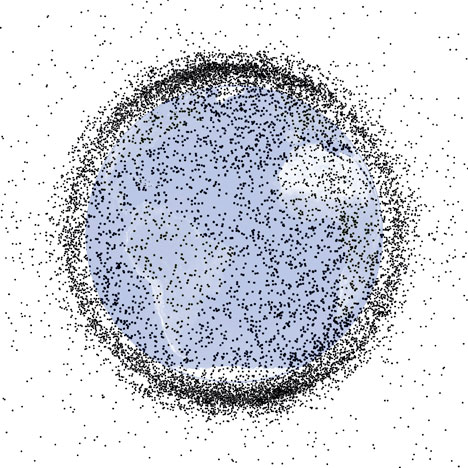

Artwork showing space debris in low and geostationary Earth orbit. Space debris includes thousands of inactive satellites, fragments of broken up spacecraft and equipment lost by astronauts. This artwork is based on density data, but is not to scale.

Orbital Objects

The skies above Earth are teeming with manmade objects large and small. The U.S. Space Surveillance Network uses radar to track more than 13000 such items that are larger than four inches (ten centimeters). This celestial clutter includes everything from the International Space Station (ISS) and the Hubble Space Telescope to defunct satellites, rocket stages, or nuts and bolts left behind by astronauts. And there are millions of smaller, harder-to-track objects such as flecks of paint and bits of plastic.

Satellites

For half a century, humans have been putting satellites into orbit around Earth to serve a variety of functions. The Soviets launched the first, Sputnik 1, in October of 1957 just to prove they could. Four months later, the U.S. responded with Explorer 1.

Since then, some 2500 satellites have been sent aloft. These include Hubble and the ISS, the Russian Mir space station, the 27-satellite Global Positioning System, as well as hundreds of others that provide communications, broadcast television and radio signals, and help scientists predict weather, among many other purposes.

These man-made objects circle Earth in orbits that range from as near as 150 miles (240 kilometers) to 22500 miles (36200 kilometers) away. Satellites in low-Earth orbit, or LEO, stay within 500 miles (800 kilometers) and travel extremely fast 17000 miles an hour (27400 kilometers an hour) or more to keep from being drawn back into Earth's atmosphere. Most satellites around Earth are found in the LEO range.

Other objects are sent much farther into space and placed in what is called geosynchronous orbit. This allows the satellite to match the Earth's rotation and "hover" over the same spot at all times. Weather and television satellites are generally in this category.

Space Junk

Orbital debris, the technical term for nonfunctional and human-made space junk, includes not only whole, abandoned satellites, but also pieces of broken satellites, deployed rocket bodies, human waste, and other random objects, like the glove lost by astronaut Ed White during his historic 1965 spacewalk. The oldest known piece of orbital debris is the 1958 Vanguard 1 research satellite, which ceased all functions in 1964. One of the newest is a refrigerator-size ammonia reservoir released into its own orbit in July 2007, following a NASA decision that no other disposal options were feasible.

Like satellites, LEO debris whizzes around the planet at 17000 miles an hour (27400 kilometers an hour) or more. The orbits of these objects differ in direction, orbital plane, and speed, however?meaning collisions are inevitable. At such speeds, termed hypervelocity, even a miniscule piece of junk presents a serious hazard for satellites, spacecraft, and spacewalking astronauts.

Gravitational pull will ensure that anything we've ever put in orbit will eventually make its way back to Earth. And though thus far no one has ever been killed by reentering space debris, NASA estimates on average one piece returns to Earth each day.

NASA and other national space agencies have identified orbital debris as a serious problem and are currently devising plans to mitigate existing space junk and curb future debris.

Orbiting junk continues to threaten International Space Station (ISS).

On the eve of the first crew arrival to the International Space Station (ISS), number one on the list of priorities among scientists and officials at NASA and around the international space community is the station's safety and well-being. But there's one seemingly low-profile threat that could someday cause big trouble for the ISS: space junk.

Near-Earth orbit is full of space junk bits and pieces of metal and other materials left over from rocket shells, exploded satellites and other aged spacecraft. In fact, scientists last month were for the first time able to link a cloud of orbital debris to an exploded rocket part, adding fodder to the notion that what we put up into space could quite literally have great impact on satellites we rely on, and even threaten the lives of space explorers.

The debris cited in last week's announcement came from a Chinese Long March 4 projectile, which exploded on March 11 after five months in near-Earth orbit and was detected by the University of Chicagos space dust instrument, SPADUS. Although the detected particles were sub-millimeter in size, they are nevertheless representative of the type of space junk that can be hazardous to sensitive parts of orbiting spacecraft including the space shuttle and the ISS.

A likely target

Indeed, it may not sound like much of a threat, but small particles can puncture and seriously harm spacecraft parts. In fact, space-shuttle ground crews routinely find evidence of tiny space particles having dug themselves quite deeply into the shuttle's windows after a mission.

"We get hit regularly on the shuttle," said Joseph Loftus, assistant director of engineering for NASA's Space and Life Science Directorate. "We've replaced more than 80 [shuttle] windows because of debris impacts."

Of course, tiny particles are just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to orbital debris. Thousands of other "junk" objects, ranging in size from inches to feet (millimeters to meters) across, loom several hundred miles (kilometers) above Earth. And these objects arent standing still. Theyre orbiting Earth just like other satellites, often at speeds of up to several miles (kilometers) per second. Crash one or more of these objects into a spacecraft or an astronaut out on a spacewalk, and you could end up with Swiss cheese serious damage.

Today, the ripest target for orbital debris appears to be the ISS, as it is slated to be the largest and most sophisticated object ever assembled in space. Add to that fact engineers expectation that the ISS will function for at least 20 years, and some experts say the station may be a disaster waiting to happen.

"When you roll it all up, the probability of the ISS getting hit by something other than very small stuff becomes nonzero," said Nicholas Johnson, chief scientist for orbital debris at NASAs Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas. "That means you really need to take some countermeasures."

Keeping track of space junk

Fortunately, both NASA and other space agencies have already made tremendous efforts to curb space-junk encounters. At the most rudimentary level, the U.S. Space Command keeps track of many of the objects orbiting Earth, including debris. As of June 2000, the total number of trackable space objects including 90 space probes, 2671 satellites and 6096 pieces of space junk was a whopping 8927.

If any of the more than 6000 space-junk objects gets too close for comfort to a satellite or inhabited spacecraft, the Space Command sends out a warning. Already, the ISS has had to move out of the way of an oncoming piece of space debris; in October 1999, ground controllers successfully maneuvered the ISS out of the way of a piece of debris that was headed right for the station. The space shuttle has also had to make way for a number of pieces of space junk.

But the Space Command can only detect particles larger than the size of a typical melon. So although engineers have developed special shielding materials to protect against the tiniest of debris, intermediate sized objects, from about half an inch to five or six inches (1 to 15 centimeters) across, become the biggest hazard of all for orbiting spacecraft.

"That gap represents the true risk to the space station," said Johnson. "Those [intermediate-sized] objects are too small to be tracked but too large to be protected against with shielding. So if we get hit by a particle in that size regime, some damage will occur."

Just how much damage depends on where and how the impact takes place. The most likely event, according to Johnson, is a small penetration, which poses a low risk to those living inside. But a worst-case scenario could easily cause cosmonauts and astronauts occupying the station to immediately evacuate the damaged module or else risk suffering from depressurization, loss of oxygen and, eventually, unconsciousness.

High-tech solutions

Thankfully, space explorers of the future may not need to worry so much about space-junk collisions. Already in the works for NASA are several projects aimed at solving the orbiting-debris problem.

The most well-known of these projects is the Orion Project, a major study which began in the late 1970s, and which continues to undergo development with help from NASA and other government agencies. The focus of Orion has been to look at the possibility of using high-powered laser-light beams to actually deflect orbital debris out of the way of spacecraft and into the Earths atmosphere where it can burn up out of harms way.

Though several major schemes have floated around since the Orion Project first began, the most feasible seems to be a ground-based laser system that would hunt down space junk and shine its laser at the particle for several minutes. The energy of the laser light would actually ablate a tiny layer on the debris surface, thus creating a thrust for the object as the molecules in the thin layer expand away from the object while theyre being vaporized.

"We have demonstrated that a laser pulse can indeed move orbital debris-like material in a vacuum", said project scientist and Orion program manager Jonathan Campbell. "If we can work on a piece of debris for several minutes, then we can tease it into the atmosphere and let the atmosphere take care of it for us".

Another idea was to have an in-situ laser on board a craft such as the ISS, which would essentially work the same as a ground-based laser, but would have the added benefit of being much closer to the actual debris.

However, two major problems with this model (referred to by some as a "laser-broom model") suggest the approach would never work: the system would take more power than the entire space station has and humans wouldnt have enough time to detect and hunt down an object coming over the horizon before it either hits or passes the craft.

"Doing it in orbit is theoretically possible, but from a systems-development management point of view, its not very practical," said Loftus.

Accordingly, scientists and engineers are working primarily on the former Orion model, and are hopeful they will soon get to test out the concept using a special laser system in Hawaii. "If we can demonstrate that we can detect a tennis-ball-sized object 2 kilometers (1.2 miles) away, and we can hold a laser beam on it through turbulent atmosphere, then that should be enough to prove to even the greatest skeptics that this is something that can be done", said Campbell.

Of course, the other obvious way to reduce space junk is to send less of it up in the first place. Currently about 200 objects per year are added to the space environment around Earth. But with more and more emphasis placed on space business and science, it seems likely that the upward trend toward more space debris will only increase.

For now, NASA and other members of the international space community are trying to fight space junk by keeping the debris in check as much as possible. Already, there are a number of design requirements and procedures for each launch and space mission that ensure the least amount of space junk, including controlled deorbiting of aging spacecraft. But people working with the Interagency Debris Corps Working Group, who look at managing orbital debris, are already looking ahead to create even better standards.

"Were trying to get international consensus", said Loftus. "So far were making very significant progress".

Orbiting junk causes International Space Station evacuation.

March, 2009

Cosmonaut Yury Lonchakov and astronaut Mike Fincke work on the exterior

of the International Space Station during a spacewalk.

That was a close call

The two American astronauts and one Russian cosmonaut aboard the International Space Station had to duck for cover Thursday as space debris passed perilously close to the orbiting platform.

Crew members Sandra Magnus, Michael Fincke and Yury Lonchakov were ordered into one of the Soyuz TMA-13 escape capsules at 12:35 p.m. EDT, and given the all-clear 10 minutes later.

In case the space station was hit, the astronauts could have undocked and headed back to Earth. Even a tiny hole could have caused a catastrophic loss of air pressure and rendered the station uninhabitable.

The debris, part of a mechanism to put a satellite in proper orbit, measured about 5 inches, a size that "will wreck your whole day," said Mark Matney, an orbit debris scientist for NASA.

"We were watching it with bated breath," Matney told The Associated Press. "We didn't know what was going to happen."

Normally, the space station would have fired its positioning thrusters to get out of the way of any oncoming objects, but NASA said the news of the possible collision came too late for that.

Matney, who's been with NASA since 1992, said it was the closest call he can remember.

The debris was expected to come within the 2.8-mile-wide box of space around the station that makes up NASA's danger zone, said NASA spokesman Kyle Herring.

"We were looking out the Soyuz window," Fincke radioed to Houston. "We didn't see anything of course. We were wondering how close we were."

Because the U.S. Strategic Command, which monitors space debris, could not get a good enough look at the debris, NASA may never know exactly how close it came, said NASA spokesman Josh Byerly. It was traveling 5.5 miles per second -- about 20,000 mph, he said.

The debris is likely a small weight followed by a 39-inch string or strand that was used to stabilize a global positioning satellite placed in orbit in May 1993, said Harvard astrophysicist Jonathan McDowell, who tracks all objects in orbit.

One of the reasons NASA got such late warning on the debris is that it is an unusual orbit that keeps dipping into the atmosphere and changing, McDowell said. It was in the worst kind of orbit to track, Matney said.

The GPS satellite went out of daily use in January, McDowell said.

Thousands of pieces of "space junk" orbit the Earth, so much that it's getting to be a problem.

The 2007 deliberate destruction of a satellite by China added hundreds of pieces, and the collision last month of an American commercial communications satellite and a dead Russian satellite only made it worse.

NASA is even considering scrapping an upcoming shuttle mission to repair the Hubble Space Telescope because the telescope orbits at an altitude close to the trails of debris left by the satellite collision.

The space station orbits at a lower altitude and is generally not at risk from space debris.

Space shuttle Discovery was to have launched from Cape Canaveral Wednesday evening for arrival at the space station Friday, but the launch was postponed to at least Sunday due to an unexpected hydrogen leak.

Meanwhile, one retired rocket scientist has proposed sending up giant squirt guns to blast water at space debris, sending each piece to such a low orbit that it would fall into the atmosphere and burn up.

Space so full of junk that a satellite collision could

destroy communications on Earth. - May 2010

Space is so littered with debris that a collision between satellites could set off an uncontrolled chain reaction capable of destroying the communications network on Earth, a Pentagon report has warned.

The volume of abandoned rockets, shattered satellites and missile shrapnel in the Earths orbit is reaching a tipping point and is now threatening the $250 billion (£174bn) space services industry, scientists said.

A single collision between two satellites or large pieces of space junk could send thousands of pieces of debris spinning into orbit, each capable of destroying further satellites.

Global positioning systems, international phone connections, television signals and weather forecasts are among the services which are at risk of crashing to a halt.

This chain reaction could leave some orbits so cluttered with debris that they become unusable for commercial or military satellites, the US Defense Department's interim Space Posture Review warned.

There are also fears that large pieces of debris could threaten the lives of astronauts in space shuttles or at the International Space Station.

The report, which was sent to Congress in March and not publicly released, said space is "increasingly congested and contested" and warned the situation is set to worsen.

Bharath Gopalaswamy, an Indian rocket scientist researching space debris at the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, estimates that there are now more than 370000 pieces of junk compared with 1100 satellites in low-Earth orbit (LEO), between 490 and 620 miles above the planet.

The February 2009 crash between a defunct Russian Cosmos satellite and an Iridium Communications Inc. satellite left around 1,500 pieces of junk whizzing around the earth at 4.8 miles a second.

A Chinese missile test destroyed a satellite in January 2007, leaving 150000 pieces of debris in the atmosphere, according to Dr Gopalaswamy.

The space junk, dubbed an orbiting rubbish dump, also comprises nuts, bolts, gloves and other debris from space missions.

"This is almost the tipping point", Dr Gopalaswamy said. "No satellite can be reliably shielded against this kind of destructive force".

The Chinese missile test and the Russian satellite crash were key factors in pushing the United States to help the United Nations issue guidelines urging companies and countries not to clutter orbits with junk, the Space Posture Review says.

The United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA) issued Space Debris Mitigation Guidelines last year, urging the removal of spacecraft and launch vehicles from the Earths orbit after the end of their missions.

Mazlan Othman, director of UNOOSA, said space needs "policies and laws to protect the public interest".

He added: We should have all the instruments to make sure that lifestyles are not disrupted because of misconduct in space when people switch the television to watch the World Cup next month in Johannesburg".

Clearing Space Junk from Earth's Orbit by Launching Water At It?

September 2009

Of all the strange ideas I've heard, this tops the list. The amount of catalogued space debris within our planet's orbit increased by nearly 50% since 2007, so DARPA wants to gather ideas for how to clear space junk from Earth's orbit. James Hollopeter of GIT Satellite lends one idea - launch rockets full of water out to space.

The idea is to sent rockets loaded up with water into space, release it, and create a wall of water that orbiting junk would bump into, slow down, and fall out of orbit. According to Discovery News, "Launched on ballistic flight paths that quickly re-enter the atmosphere, the water wouldn't add to the debris problem, unlike some other proposals to clean up space. The so-called Ballistic Orbital Removal System could be operated inexpensively by launching water on decommissioned missiles out of suborbital launch complexes, such as NASA's Wallops Island in Virginia, he added".

It sounds like a joke, especially when we consider the water crisis and many other major global issues down here on terra firma, but Hollopeter insists that if paperwork were pushed through NASA, he could get a test operation done in 18 months. Maybe with rising sea levels, we could just launch all the extra ocean water into space and not have to worry about ghost states! *eye roll* Questions that come up off the cuff include how much water this would take, and how much fossil fuel would be used to launch enough water up there to clear out the junk?

At any rate, DARPA wants any and all ideas, since the problem of orbiting space junk is getting ridiculous, with over 20,000 trackable objects catalogued so far and 94% of it being classified as debris.

Beware Of Space Junk

December 2009

Global warming isn't the only major environmental problem.

As world leaders meet in Copenhagen to consider drastic carbon emission restrictions that could require large-scale de-industrialization, experts gathered last week just outside Washington, D.C., to discuss another environmental problem: space junk. Unlike with climate change, there's no difference of scientific opinion about this problem-orbital debris counts increased 13% in 2009 alone, with the catalog of tracked objects swelling to 20000, and estimates of over 300000 objects in total; most too small to see and all racing around the Earth at over 17500 miles per hour. Those are speeding bullets, some the size of school buses, and all capable of knocking out a satellite or manned vehicle.

At stake is much more than the $200 billion a year satellite and launch industries and jobs that depend on them. Satellites connect the remotest locations in the world; guide us down unfamiliar roads; allow Internet users to view their homes from space; discourage war by making it impossible to hide armies on another country's borders; are utterly indispensable to American troops in the field; and play a critical role in monitoring climate change and other environmental problems. Orbital debris could block all these benefits for centuries and prevent us from developing clean energy sources like space solar power satellites, exploring our Solar System and someday making humanity a multi-planetary civilization capable of surviving true climatic catastrophes.

The engineering wizards who have fueled the Information Revolution through the use of satellites as communications and information-gathering tools also overlooked the pollution they were causing. They operated under the "Big Sky" theory: Space is so vast, you don't have to worry about cleaning up after yourself. They were wrong. Just last February, two satellites collided for the first time, creating over 1500 new pieces of junk. Many experts believe that we are nearing the "tipping point" where these collisions will cascade, making many orbits unusable.

But the problem can be solved. Thus far, governments have simply tried to mandate "mitigation" of debris creation. But just as some warn about "runaway warming," we know that mitigation alone will not solve the debris problem. The answer lies in "remediation": removing just five large objects per year could prevent a chain reaction. If governments attempt to clean up this mess themselves, the cost could run into the trillions-rivaling even some proposed climate change solutions.

Instead, space-faring nations should create an Orbital Debris Removal and Recycling Fund (ODRRF). Satellite operators would pay relatively small fees to their governments, who would contribute the money to the fund. These governments already charge satellite operators large licensing and regulatory fees. Private companies would be paid bounties out of the fund for successfully removing debris according to the debris-creation-avoidance value assigned to each object. Apart from the obvious long-term benefits of preserving the usability of the space environment, satellite operators would benefit in the short term from reduced insurance rates and fewer mysterious satellite outages caused by collisions we cannot track. With the right funding mechanism, entrepreneurs can solve this problem. Governments must encourage innovation rather than crippling industry or creating yet another large government program to build and operate systems when the expertise for doing so clearly resides in the private sector.

Better tracking data would be required to maximize the effectiveness of debris removal prizes. Since much of that data is classified, only a trusted intermediary could get American and Russian defense officials to work together. But the largest obstacle is legal: While maritime law encourages the cleanup of abandoned vessels as hazards to navigation, space law discourages debris remediation by failing to recognize debris as abandoned property, and making it difficult to transfer ownership of, and liability for, objects in space-even junk. By adapting maritime precedents, space law could make orbital debris removal feasible, once the right economic incentives are in place. Entrepreneurs may even find ways to recycle and reuse on orbit the nearly 2000 metric tons of space debris, which includes ultra-high grade aerospace aluminum and other precious metals.

We must solve the orbital debris problem, if only so that satellites can continue collecting the climate data we need to make informed decisions about carbon emissions. But how we solve this problem should offer valuable lessons for all environmental policymaking. All this cause needs is a champion who can rally policymakers in the U.S. and abroad, not with scare tactics but with a relentless optimism about the power of entrepreneurs to solve even the most difficult environmental problems through innovation, and about the bright promise of humanity's future-on earth and in space.

Space Junk Fears Grow

May 2010

Satellites face threat of 370000 pieces of orbiting trash

Space Shuttle Atlantis orbits the Earth on May 15 with its cargo bay door open. Space junk is orbiting with it, traveling at a speed of nearly five miles a second.

"We certainly hope that there will be no further irresponsible acts such as targeting satellites with weapons."

Trash in space may bring commerce and communications on Earth to a halt unless policy makers and executives take steps to prevent satellite collisions with orbiting junk, according to a Pentagon report.

Potential crashes between satellites and debris refuse from old rockets, abandoned satellites and missile shrapnel are threatening the $250 billion space-services market providing financial communication, global-positioning navigation, international phone connections, Google-Earth pictures, television signals and weather forecasts, the report says.

Space is increasingly congested and contested, said the U.S. Defense Departments interim U.S. Space Posture Review, which was sent to Congress in March and not publicly released.

Scientists are warning that space collisions could set off an uncontrolled chain reaction that might make some orbits unusable for commercial or military satellites because they are too littered with debris. The February 2009 crash between a defunct Russian Cosmos satellite and an Iridium Communications Inc. satellite left 1500 pieces of junk, each whizzing around the Earth at 4.8 miles a second and each capable of destroying more satellites.

This is almost the tipping point, Bharath Gopalaswamy, an Indian rocket scientist researching space debris at the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, said in an e-mailed response to questions. No satellite can be reliably shielded against this kind of destructive force.

A Chinese missile test destroyed a satellite in January 2007, leaving 150000 pieces of junk in the atmosphere, according to Gopalaswamy. That test was a central factor in pushing the U.S. to help the United Nations issue guidelines urging companies and countries not to clutter orbits with junk, the Space Posture Review says.

Nobody recognized this as a big issue until a few years ago, said Chris Kunstadter, vice president of insurance operations at XL Capital Ltd., a New York-based company selling satellite policies. The Chinese interceptor test and the Iridium incident opened our eyes.

In low-Earth orbit, between 800 and 1000 kilometers above the planet, there are now more than 370000 pieces of junk, compared with 1100 satellites, Gopalaswamy estimates. The U.S. Space Posture Review, the second produced since 2007, forecasts orbital congestion will worsen.

Space needs policies and laws to protect the public interest, UN Office on Outer Space Affairs Director Mazlan Othman said in an interview. We should have all the instruments to make sure that lifestyles are not disrupted because of misconduct in space when people switch the television to watch the World Cup next month in Johannesburg.

We are seeing an increasing number of incidents when operators have to maneuver their satellites to avoid a piece of debris, David Wade, an underwriter at London-based Atrium Space Insurance Consortium, said. Performing these maneuvers consumes additional fuel and reduces the lifetime of the satellite.

XL and Atrium, a partner with Lloyds of London, say that the higher risk of satellite collisions with debris hasnt yet led to higher premium payments.

Communications satellites at altitudes of 36000 kilometers also face space debris problems. Companies sometimes resort to gentlemens agreements through the UNs International Telecommunications Union under which they temporarily rely on satellites from competitors when services are threatened, Yves Feltes, a spokesman for SES SA, the worlds biggest publicly traded satellite operator, said.

A satellite operated by Luxembourg-based SES was threatened by an out-of-control Intelsat-Galaxy-15 satellite in May. Intelsat S.A.s satellite interfered with the transmission frequency of an SES space asset after Earth-bound technicians couldnt regain control over the Galaxy-15.

Intelsat and SES are both pioneers in the commercial uses of space. Intelsat began transmitting signals in 1965, the result of a law signed by President John F. Kennedy giving private companies access to space. SES was launched in 1985 as Europes first private satellite network.

We are working closely with SES, and have been since the early days of the anomaly, to minimize the interference that could be caused by the satellite as it flies by other satellites, Intelsat spokeswoman Dianne VanBeber said. The closely held company may have to take an impairment loss for the Galaxy-15 satellite, valued at $142 million, Intelsat said May 12.

Any outage due to an unexpected technical or health problem usually leads to credits to the customers for compensation, SES says on its website. An hour of outage for a satellite can cost as much as $150000.

TV viewers may face programming interruptions unless rival companies adjust to the defunct Intelsat satellites orbit, according to the UN. The incident highlights the need for tougher regulations.

Satellites are becoming an ever greater part of our everyday lives, Wade said. We certainly hope that there will be no further irresponsible acts such as targeting satellites with weapons which would increase the debris threat even further.

TrackingSat GPS - Satellite Dish Alignment Tools.

TrackingSat is useful to assist users that need to install

your antenna and align it with the satellites in orbit.

If you want to exchange links to increase PR, contact us.

Satellite Dish Alignment Tools